In a world often fractured by conflict, the path to peace might seem distant—residing in diplomatic halls or social movements.

Yet, what if a far-reaching step toward harmony begins much closer to home, right in our own kitchens?

As a food journalist, a vegetarian chef, and a sustainable lifestyle advocate with a Master’s degree in Human Rights, Conflict, and Peace Studies, I believe deeply that our food choices carry the seeds of both discord and serenity.

The concept of a “conflict-free” kitchen extends beyond simply avoiding war-zone minerals.

It is about consciously cultivating peace, ethical responsibility, and holistic well-being through every ingredient we select and every meal we prepare.

For true inspiration, we need look no further than the rich indigenous food traditions of Ghana.

Although modern global food systems provide abundance, they are often entangled in a web of conflicts: environmental degradation, exploitative labor practices, unsustainable resource depletion, and the marginalization of local economies.

The global mango trade, for instance, serves as a potent illustration of how the pursuit of cheap, abundant food creates a “web of hidden conflicts.”

According to World Economic Forum and CrowdFarming estimations, the production of one kilogram of mangoes uses approximately 1,600 liters of water out of the global average water consumption footprint of roughly 3,800 liters per person per year.

On the other hand, the global demand for low-cost, unblemished fruit drives down wages and often involves hazardous working conditions disproportionately affecting vulnerable workers.

A joint global report by the International Labour Organisation and UNICEF reveals that agriculture is the largest sector for child labor, accounting for 61% of all child labourers, and nearly 60% of children engaged in hazardous work (dangerous tasks that can harm health, safety, or development) are found in the agriculture sector.

When it comes to the supply chain of other common global commodities like cocoa (which shares similar labour issues), the average smallholder farmer in major producing countries such as Ghana often earns as little as 40% of a living income, forcing reliance on children for labour.

A “conflict-free” kitchen, therefore, is one where we actively seek to minimize this impact, favouring practices and ingredients that promote ecological balance, social justice, and personal health.

This journey toward culinary peace finds a profound blueprint in indigenous Ghanaian food habits.

Ghanaian cuisine, often misunderstood or overshadowed by global trends, is a treasure trove of healthy, sustainable, and inherently conflict-reducing practices.

It is a food culture deeply rooted in respect for the land, community, and the inherent nutritional wisdom of nature.

In many Ghanaian ethnic groups, specific dietary taboos were historically enforced by traditional authorities, creating a powerful non-legislated form of ecological and food system management.

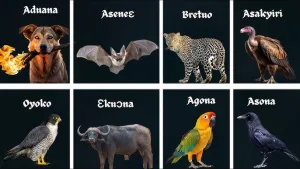

Taboos often target specific fauna species (such as certain monkeys, large reptiles, or fish) that are revered as totems or linked to ancestral myths.

This provided crucial protection for endangered or vulnerable animals, preserving biodiversity that maintains a healthy ecosystem for other food sources.

Based on anthropological and ethnobotanical studies regarding traditional dietary practices and taboos in Ghana, the Ashanti, part of the larger Akan group, traditionally practice various totemic taboos (akyiwadeɛ).

Ashanti clans that identify with a specific totem animal—such as the python, vulture, or specific types of fish—forbid their members from eating, harming, or even touching that animal, as the totem is believed to represent their ancestors or embody the spirit of the clan.

This practice among the Ashanti and other ethnic groups in Ghana serves as a form of species conservation within their traditional territories, promotes nutritional sustainability by diversifying the diet away from a single vulnerable protein source, and encourages consumption of more plentiful, fast-reproducing species.

This ensures the long-term viability of the food supply rather than short-term exploitation that places pressure on particular wildlife populations.

Also, the fear of spiritual consequence or community sanction acts as a highly effective behavioral control mechanism, ensuring compliance and internalizing the concept of environmental preservation within the culture, rather than imposing it externally.

In a conflict-free kitchen, mindful eating and communal meals become the architecture of a peace plate.

Food in Ghana is often a deeply communal affair, eaten slowly and with appreciation.

This collective and mindful approach contrasts sharply with the rushed, individualistic, and often distracted eating habits prevalent in many modern societies, where meals are consumed standing up or while staring at a mobile phone or television screen.

Eating together, sharing stories, and savoring each bite foster social cohesion and reduce the stress and detachment that can lead to unhealthy eating patterns and social isolation.

This communal aspect is a direct antidote to the social conflicts of solitude and disconnection.

As a Ghanaian, specifically from Tamale in the Northern Region, a classic example of this mindful tradition is the act of sharing a large bowl of Tuo Zaafi (TZ) served with vibrant green ayoyo (jute leaves) soup with my family or friends.

In this practice, individuals gather around a single or double serving dish, using their right hand to scoop and mold a portion of TZ before dipping it into the shared soup.

This requires unspoken coordination, patience, and mutual respect to ensure everyone gets a fair share of the food, especially the protein (meat, fish, or mushrooms).

This communal practice is also an engaging process that forces participants to be present, savor the texture and taste, and connect with those immediately around them.

In this simple act, the table transforms into a space for relationship-building and collective peace, reinforcing the truth that food is meant to nourish not just the body, but the community as well.

This path supports the ecological system, strengthens community bonds through food, promotes social justice, and encourages mindful consumption.

The daily act of cooking is thus transformed from a routine chore into a profound act of stewardship, where every species preserved, every local farm supported, and every communally shared meal becomes a vote for harmony.

Let the only sound of conflict in your kitchen be the sizzling of a prepared guilt-free dish, cultivating a peace treaty from the plate to the planet.

The writer is a food journalist, certified vegetarian chef and a sustainable lifestyle advocate.

Website: hawassustainablejournal.com

Email: greencornish13@gmail.com

WhatsApp: 0573980740